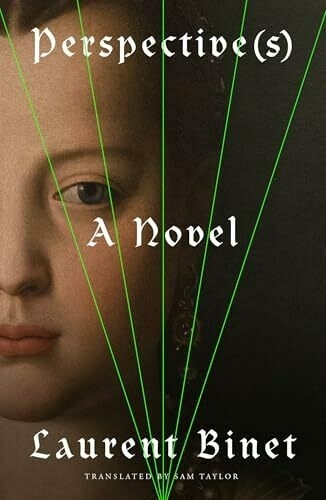

Nasty rumours, intricate plots, boldfaced lies, declarations of love, and accusations of murder—letters containing all these flit across Renaissance Italy in Laurent Binet’s epistolary “Perspective(s)” (translated by Sam Taylor, 2023). With a plot as finely woven as a tapestry, we follow Giorgio Vasari, artist and attack dog for Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, investigating the murder of Jacopo da Pontormo in the chapel of San Lorenzo, where he’s been working on a divisive fresco for 11 years.

Jacopo is found with a chisel in his heart. A section of his fresco seems to have been repainted by someone skilled enough to emulate the old master, but not to avoid detection. Duke Cosimo tasks Vasari, a real-life painter and chronicler of Renaissance artists, with finding the murderer. What follows is a whodunit mystery told through 176 letters from 20 larger-than-life characters pulled straight from the art history books.

Both paintings in this story are scandalous. Jacopo’s fresco is controversial due to its mannerist style, with elongated nude figures and depthless spaces. Vasari, a fan of traditional perspective and chronicler of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, calls it “truly awful.” The other is a nude Venus with the face of Duke Cosimo’s 17-year-old daughter, Maria de’ Medici—a humiliation for the Medici family that threatens her marriage prospects.

When Catherine de’ Medici, Queen of France and Maria’s aunt, learns of the Venus painting, she sees a political opportunity. She plans to steal it, make copies, and distribute them through Europe, undermining Cosimo’s authority.

This Renaissance scandal involving non-consensual imagery of a young woman feels relevant today. Almost 500 years later, our society still grapples with similar ethical questions—now in the form of AI-generated deepfakes instead of oil paintings. Last week, the “Take it Down Act” passed in US Congress, aiming to curb this type of violation. Through his historical fiction, Binet challenges the notion that privacy concerns are uniquely modern or tied to a particular medium.

The epistolary format—a bold choice that could have been dull in lesser hands—privileges us with information the characters don’t have. This use of dramatic irony keeps us engaged despite the fragmented structure. When Catherine learns that Maria, unhappy with her political betrothal to the Duke of Ferrara, has an affair with her father’s page, she encourages her niece to follow her heart and elope to France. Sweet, right? Not quite. Catherine’s other letters show she’s content to ruin her niece’s life to harm her nemesis, Cosimo. And ruin it she does.

Maria’s tragic tale contrasts with absurd levity. The novel oscillates between political intrigue and cinematic action, as when Vasari uses perspective painting technique to fire his crossbow right between the eyes of an attacker.

The letters by Benvenuto Cellini, the flamboyant and braggadocious thief Catherine hires to steal the Venus painting, are a treat. “God must love you, Madame,” he says to Catherine, “for he has placed me upon your path.”

That’s certainly one way to address a sitting queen.

“Perspectives” is a salacious, laugh-out-loud delight written in crisp, witty prose that makes even art history novices feel in on the joke. Binet reveals the worst behaviour of major historical figures through language that feels both period-appropriate and accessible. “What a drag!” says Maria at one point, but this novel is anything but.

Readers of historical fiction will appreciate this novel, especially those interested in art history or Renaissance politics. Even those less familiar with the period will be engaged by the themes of power, privacy, and consent that remain urgent today.